|

| Early morning, a Zero squadron heading to Okinawa flies by the Kaimondake volcano - Pol, digital Watercolour |

The small town of Chiran was chosen as the training base for the pilots of the Japanese Airforce since 1941, after Pearl Harbor. Being on the southernmost tip of Japan, it became the base of the suicide squadrons in 1945 that would defend Okinawa: the "gate of Japan". More than a thousand pilots will take off from this base and greet Mount Kaimondake, a mini Mount Fuji located 30 kms south on the Pacific Coast, on their way somewhere between Chiran and Okinawa where they will perish.

The Air base was located right at the present site of the Museum of Peace devoted to the Kamikazes. Located on a promontory south of town, it dominated the narrow valley where cultures and manicured rows of green tea were spread out: well-ordered, fresh and acid coloured rectangles of land, set on all sides by small verdant hills of exuberant flora. The small town of Chiran is built along the Fumoto river. Starting from the city center, Bukeyashini Street stretches to the east and is bordered by samurai houses and their magnificent gardens designed by the master gardeners of Kyoto. These remains of traditional Japan have survived all the cataclysms and participate in the mythological atmosphere, somewhere out of time, of this small isolated and foggy valley. Today the main street is bordered, on either side of its extension towards the south from the entrance of the city to the museum of peace, by a thousand stone lanterns symbolizing each of the disappeared pilots.

|

| Chiran Valley |

|

| Neglected tea plantation (Samurai Quarters) |

l

|

| Commemorative Lantern |

|

| Bambou Forest on the way to the Peace Museum |

Samurai Quarters

|

| I suppose Pilotes would come here trying to find a purpose to all this nonsense ... |

Tome's Place

Besides the Air Base and the Samurai Street, Chiran has another historic attraction: the restaurant of Mrs. Torihama, familiarly named ”Tome’s Place”. When the flight school commander asked Chiran’s chief of police what the best restaurant in town was, the chief scratched his head and said he didn’t know, but the friendliest was Torihama Tomé’s. The next day a sign hung from Tomé’s doors: Military Designated Restaurant.

The pilots, some as young as fourteen, staggered into Tomé’s on Sundays. Homesick, exhausted from the training, they slumped behind the tables. Many had never been in a restaurant before. This woman in her forties, Torihama Tomé, quickly became their adoptive mother. They called her Obachan, “little mother,” a pet name full of affection, reserved for older women. For many of these young men, she was their last link to humanity. A consoling confident, she undertook the mission to transmit the farewell letters of the suicide bombers to their families. Her daughter, Reiko, testified that she saw the secret police (the Kempetai) taking her mother away several times. She would spent the night at the police station and returned the next day with a swollen face. By transmitting the letters of the pilots she was bypassing the military censorship. Torihama San died in 1992 at the age of 89. She continued to serve the American marines in her restaurant in Chiran, just after the war. Considered today as a heroine, one can see in town her bronze statue. The restaurant has become a small museum-temple to her memory. Reiko (her daughter) opened a small restaurant in Tokyo after the war, where Chiran air base veterans were to meet. **

** The former Japanese Kamikazes spoke of the Tokko syndrome where they became socially excluded (somewhat like Vietnam Vets in USA) and confronted daily with the post war repugnance of the Japanese people for the suicide missions program (Divine Wind: An Interview with Atsushi Takatsuka (former kamikaze) - Ryo Wanabe. Cabinet) Some turned into bandits, as henchmen for the Yakuza, the new Samurais of Japan (The 70s manga: Kawaguchi's Black Sun (Kuroi Taiyou)).

The pilots, some as young as fourteen, staggered into Tomé’s on Sundays. Homesick, exhausted from the training, they slumped behind the tables. Many had never been in a restaurant before. This woman in her forties, Torihama Tomé, quickly became their adoptive mother. They called her Obachan, “little mother,” a pet name full of affection, reserved for older women. For many of these young men, she was their last link to humanity. A consoling confident, she undertook the mission to transmit the farewell letters of the suicide bombers to their families. Her daughter, Reiko, testified that she saw the secret police (the Kempetai) taking her mother away several times. She would spent the night at the police station and returned the next day with a swollen face. By transmitting the letters of the pilots she was bypassing the military censorship. Torihama San died in 1992 at the age of 89. She continued to serve the American marines in her restaurant in Chiran, just after the war. Considered today as a heroine, one can see in town her bronze statue. The restaurant has become a small museum-temple to her memory. Reiko (her daughter) opened a small restaurant in Tokyo after the war, where Chiran air base veterans were to meet. **

** The former Japanese Kamikazes spoke of the Tokko syndrome where they became socially excluded (somewhat like Vietnam Vets in USA) and confronted daily with the post war repugnance of the Japanese people for the suicide missions program (Divine Wind: An Interview with Atsushi Takatsuka (former kamikaze) - Ryo Wanabe. Cabinet) Some turned into bandits, as henchmen for the Yakuza, the new Samurais of Japan (The 70s manga: Kawaguchi's Black Sun (Kuroi Taiyou)).

|

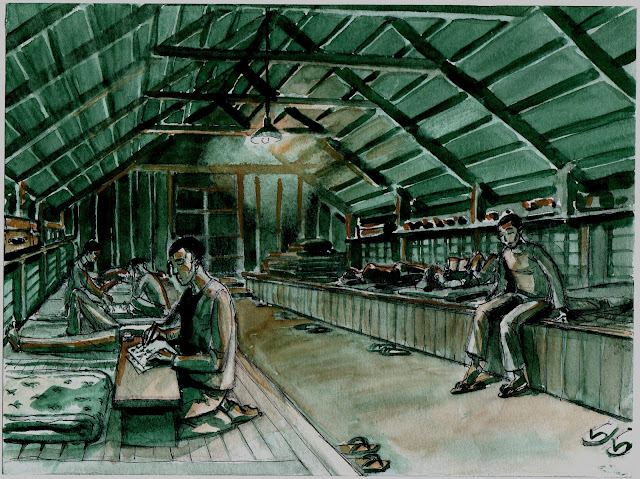

| Tome's museum, quite true to the 1945 restaurant |

|

| Tome serving the cadets in her restaurant - Pol, watercolour |

|

| Tome's Place strip - Pol, Watercolour |

Chiran Peace Museum

|

| Chiran Peace Museum |

|

| Chiran Museum Entrance : The goddesses embark the deceased Kamikaze in Heaven ... This reminds me of something |

|

| Tadamasa Itatsu |

Like many survivors of Tokko Missions, Itatsu San suffered from the Lazarus syndrome. Condemned to a certain death he did not bear having survived while so many others died. He began collecting letters (more than a thousand) and memories of his missing fellow combatants. Today this collection is exhibited in the museum. The original intention of the museum is very commendable; Keep the memory of these sacrificed lives alive so that it does not happen again in the future. What has particularly disturbed me here and in most of these museums devoted to suicide bombers, known as museums of peace, is that one seems to confuse bellicose and patriotic pride with denunciation of unforgivable events. The way of exposing and documenting the feats of these pilots makes one question the (real) intentions of the museums ...

I will talk in more details about this particular point in my article on the Yushukan Temple in Tokyo (coming soon).

As for the contents of the letters, I have translated here a quote from the article of Rafaële Brillaud of "Histoir” magazine based on the book of Emiko Ohnuki-Tierney:

"Chiran's letters testify that only a few pilots took off with joy in their hearts. "When the operation was instituted not one officer of the military schools volunteered," Emiko Ohnuki-Tierney wrote. They were only too convinced of the absurdity of this death. "The suicide bombers were teenage pilots, usually simple soldiers, followed by nearly a thousand students whom the government certified in a rush in order to send them fight right away.

|

| Artefacts and letters, Chiran Museum |

|

| Artefact - Chiran Museum |

|

| Kamikaze Pilote Portraits displayed in date of death order - Chiran Museum |

|

| Pilot Sketch Book - Chiran Museum |

I translate here two other Quotes of the article of Le Monde of February 14th 2007, “Kamikazes in spite of them” of Philippe Pons, who reports on WWII Japanese suicides missions:

"The success rate was low: barely 10% hit their target. The pilots sometimes had less than 100 hours of flight, recalls Iwao Fukagawa. Often their aircrafts were "flying coffins" due to their poor mechanical condition and lack of fuel to return trip. One of the most experienced pilots, Shigeyoshi Hamazono, who survived, did not hide his rancor against the leaders who did not leave: he recalled, in the daily newspaper Asahi Shimbun, that going to his plane, On April 6, 1945, he drank sake at the bottleneck and taking control of the plane, he shouted: “Gang of Mor ..."

Speaking of the volonteering: “There were certainly maniacs among them, but the great majority left because they had no choice. "We were comforted by the idea that at least we would be heroes," notes one of them in his diary. According to Hideo Den, who survived, "it is despair that led us".

Volunteers? "We were supposed to be." In reality, we were appointed and it was impossible to escape, the social pressure was too strong, "said Iwao Fukagawa. They were forced to volunteer "

About the letters: “The young pilots were, for the most part, cadets or student soldiers. Before leaving, they had to write an official will in which they evoked the "great cause" for which they were going to die. But in the last messages to their families, which they handed secretly to the young employees of the base, no grandiloquence.”

"It is not true that I want to die for the Emperor ... But it was decided thus for me," writes one of them. He adds that his comrades like himself had only one desire: to go back home. Once appointed, Shigeyoshi Hamazono recalls, "they fell back on themselves, and their comrades did not even dare speak to them." Unnecessary sacrifice? "They were courageous and sincere, and that is why we must honor their memory," said Iwao Fukagawa.

"The success rate was low: barely 10% hit their target. The pilots sometimes had less than 100 hours of flight, recalls Iwao Fukagawa. Often their aircrafts were "flying coffins" due to their poor mechanical condition and lack of fuel to return trip. One of the most experienced pilots, Shigeyoshi Hamazono, who survived, did not hide his rancor against the leaders who did not leave: he recalled, in the daily newspaper Asahi Shimbun, that going to his plane, On April 6, 1945, he drank sake at the bottleneck and taking control of the plane, he shouted: “Gang of Mor ..."

Speaking of the volonteering: “There were certainly maniacs among them, but the great majority left because they had no choice. "We were comforted by the idea that at least we would be heroes," notes one of them in his diary. According to Hideo Den, who survived, "it is despair that led us".

Volunteers? "We were supposed to be." In reality, we were appointed and it was impossible to escape, the social pressure was too strong, "said Iwao Fukagawa. They were forced to volunteer "

About the letters: “The young pilots were, for the most part, cadets or student soldiers. Before leaving, they had to write an official will in which they evoked the "great cause" for which they were going to die. But in the last messages to their families, which they handed secretly to the young employees of the base, no grandiloquence.”

"It is not true that I want to die for the Emperor ... But it was decided thus for me," writes one of them. He adds that his comrades like himself had only one desire: to go back home. Once appointed, Shigeyoshi Hamazono recalls, "they fell back on themselves, and their comrades did not even dare speak to them." Unnecessary sacrifice? "They were courageous and sincere, and that is why we must honor their memory," said Iwao Fukagawa.

Notes on the Kamikaze reeducation camps

|

| Chiran Museum |

Notes on the reeducation camps from the book of Sanae Sato Kojinsha : “Tokkou no machi : Chiran” (Special attack corps Town: Chiran) From the testimony of Reiko Akabane, daughter of Tome Torihama.

Chapters 8 and 9 introduce one of the darkest episodes in Japan's special attack operations. The 6th Air Army, headquartered in Fukuoka Prefecture and responsible for Chiran Air Base operations, converted the dormitory at Fukuoka Girls Academy into a building used to imprison kamikaze pilots who returned from unsuccessful suicide missions. The building is usually referred to as Shinbu Barracks, named for the Army's Shinbu Corps that carried out aerial suicide attacks, but 6th Air Army staff officers sarcastically referred to it as the "sewing rooms." Guards did not allow detained pilots to have any communication with the outside world, including their families. Even though about 50 pilots were locked up in the barracks, military records do not mention anywhere its existence. Former Lieutenant Commander Kiyotada Kurasawa, a 6th Air Army staff officer, explains why its existence was kept a strict secret, "After the kamikaze pilots became gods, there was no other way for them to keep their honor except by putting them away".

The author presents several individual examples to demonstrate the great injustice of the pilots' imprisonment in Shinbu Barracks, where staff officers subjected them to daily "reeducation" *. Many kamikaze pilots in Shinbu Barracks had survived by making forced landings near islands on the way to Okinawa after their planes developed engine problems. They were rescued from these islands, and the pilots expressed their desire to sortie on another suicide mission. Instead, they were sent to 6th Air Army Headquarters to be imprisoned in Shinbu Barracks. The author mentions a case where five pilots of one unit in Chiran could not sortie on a scheduled suicide mission due to unavailability of planes, and they too ended up in Shinbu Barracks in Fukuoka.

In another example the author writes about another wife (not named) that ran out on the airfield to stop her husband from taking off on a suicide mission. Her husband then had supposedly to wait for another available plane. However, one day his wife showed up again, grabbed his pistol, and threatened suicide. Although her husband stopped her, he then was locked away in Shinbu Barracks because of his wife's extreme actions

* Ryuji Nagatsuka relates in his book “I was a Kamikaze” his volunteering for a kamikaze special attack corps. He sortied with a group of eighteen fighters, but twelve returned to base because bad weather made it impossible to locate the American fleet. The commanding officer considered their action to be equivalent to desertion and a discredit to the squadron, so the pilots were punched in the face, put under arrest for three days, and forced to copy out the emperor's decree on military conduct.

Yashuo Kuwahara, in his book with the same title, writes about the sadistic physical bullying inflicted to the new airforce military recruits in order to break them in.

Bibliographic sources : Two books based extensively on the testimony of Tome’s daughter Reiko Akabane who served in the Nadeshiko Brigade: in charge of cleaning, mending, laundry and being part of the farewell comity addressed to the pilots leaving for their suicidal mission. Tokkou no machi: Chiran (Special attack corps town: Chiran)

by Sanae Sato Kojinsha and Hotaru Kaeru (The Firefly Returns) written by Ishii Hiroshi

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.